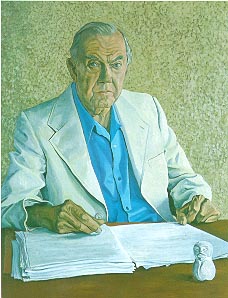

It's not often that I bother to invoke prose-fiction excerpts on this blog, mainly because they take so damned long to type out, but also because they tend to be rather difficult to segment. Graham Greene is especially tricky in this regard. A novelist well known for his technique of tying his narrative to the very specific demands of his stories, he seldom offers those sorts of paragraphs that totalize meaning, or stop to take account of the actions or the development up to a certain point in the tale. Sentences here and there are excerptable enough, but never small vignettes. But Greene is a wonderful writer, and certainly one of my favourite novelists of the twentieth century. He always seemed to probe issues that (to me, at least) were fundamental, unsettling, genuinely significant, particularly in terms of what we might all-too-blandly call "character." Simply put, I don't think enough people read enough Greene, and those that do read him tend to want to pigeon-hole him with terminology that just doesn't work. Those, for example, that think of Greene as a Catholic writer shove him into one corner; others that label him a spy-ficiton novelist shove him into another; and even those concerned with the "human dramas" at work in his books tend to shove him into the category of "harrowing, intense writer" that just doesn't work, either.

It's not often that I bother to invoke prose-fiction excerpts on this blog, mainly because they take so damned long to type out, but also because they tend to be rather difficult to segment. Graham Greene is especially tricky in this regard. A novelist well known for his technique of tying his narrative to the very specific demands of his stories, he seldom offers those sorts of paragraphs that totalize meaning, or stop to take account of the actions or the development up to a certain point in the tale. Sentences here and there are excerptable enough, but never small vignettes. But Greene is a wonderful writer, and certainly one of my favourite novelists of the twentieth century. He always seemed to probe issues that (to me, at least) were fundamental, unsettling, genuinely significant, particularly in terms of what we might all-too-blandly call "character." Simply put, I don't think enough people read enough Greene, and those that do read him tend to want to pigeon-hole him with terminology that just doesn't work. Those, for example, that think of Greene as a Catholic writer shove him into one corner; others that label him a spy-ficiton novelist shove him into another; and even those concerned with the "human dramas" at work in his books tend to shove him into the category of "harrowing, intense writer" that just doesn't work, either.  Part of what makes Greene such a wonderful writer is his flexibility, and his capacity to shift from seriousness to humour with the deftest touch. Greene, when the situation called for it and which people tend to forget, could be a very funny writer-- as so-clearly evidenced by Travels With My Aunt and Our Man In Havana. For me, though, his real personal triumph-- though many of my fellow critics describe the volume as a minor work for Greene-- is Monsignor Quixote, one of those books both whimsical and moving by turns, and one that never seems to go "too heavy" on the emotional or intellectual syrup. There's always a humour to be found--- or, as at the ending (which I'll not reveal, but which one should be able to guess if one's read Cervantes), provocatively un-sentimental, except perhaps for the book's last sentence. One might even wonder if the novel's ending has been leading us to a question the central characters address but rather haphazardly: are we all, in the end, afraid of mystery, afraid of the things we do not know or understand, even if those things mysterious may be benevolent? I wonder.

Part of what makes Greene such a wonderful writer is his flexibility, and his capacity to shift from seriousness to humour with the deftest touch. Greene, when the situation called for it and which people tend to forget, could be a very funny writer-- as so-clearly evidenced by Travels With My Aunt and Our Man In Havana. For me, though, his real personal triumph-- though many of my fellow critics describe the volume as a minor work for Greene-- is Monsignor Quixote, one of those books both whimsical and moving by turns, and one that never seems to go "too heavy" on the emotional or intellectual syrup. There's always a humour to be found--- or, as at the ending (which I'll not reveal, but which one should be able to guess if one's read Cervantes), provocatively un-sentimental, except perhaps for the book's last sentence. One might even wonder if the novel's ending has been leading us to a question the central characters address but rather haphazardly: are we all, in the end, afraid of mystery, afraid of the things we do not know or understand, even if those things mysterious may be benevolent? I wonder.I'd like to encourage all of my readers here to take the time to read through this very funny excerpt from Monsignor Quixote (see below) in which the two characters do what they do for the scope of the book--- they talk. (God forbid!) It's long, but it's worth it. Then go out and get the book--- and, by the way, even check out the BBC film version from about 20 or so years ago with the now departed Alec Guinness and Leo McKern. Enjoy--- and please pardon any typos.

Read excerpt from Monsignor Quixote

"You want to go north?" Father Quixote asked. "I thought perhaps we might at least take a little turn in the direction of Barcelona."

"I am guiding you," the Mayor said, "to such a holy site that I feel sure you will want to say your prayers there. Follow the road towards Salamanca until I tell you when to turn off."

Something in the way he spoke gave Father Quixote cause for uneasiness. He fell silent and his dream came back to him. He said, "Sancho, do you really believe that one day all the world will be Communist?"

"I believe that, yes. I shan't see the day, of course."

"The victory of the proletariat will be complete?"

"Yes."

"All the world will be like Russia?"

"I didn't say that. Russia is not yet Communist. It has only advanced along the road to Communism farther than other countries." He put a friendly hand against Father Quixote's mouth. "Don't you, a Catholic, start talking to me about human rights and I promise that I won't talk to you about the Inquisition. If Spain had been entirely Catholic, of course, there would have been no Inquisition--- but the Church had to defend herself against enemies. In a war there is always injustice. Men will always have to choose a lesser evil and the lesser evil may mean the state, the prison camp, yes, if you like to say it, the psychiatric hospital. The state or the Church is on the defensive, but when we arrive at Communism, the state will wither away. Just as, if your Church had been successful in making a Catholic world, the Holy Office would have withered away."

"Suppose Communism arrives and you are still alive."

"That's an impossibility."

"Well, imagine you had a great-great-grandson of the same character as yours and he lived to see the end of the state. No justice, no inequality--- how would he spend his life, Sancho?"

"Working for the common good."

"You certainly have faith, Sancho, great faith in the future. But he would have no faith. The future would be there before his eyes. Can a man live without faith?"

"I don't know what you mean--- without faith. There will always be things for a man to do. The discovery of new energy. And disease--- there will always be disease to fight."

"Are you sure? Medicine is making great strides. I feel sorry for your great-great-grandson, Sancho. It seems to me he may have nothing to hope for except death."

The Mayor smiled. "Perhaps we shall even conquer death with transplants."

"God forbid," Father Quixote said. "Then he would be living in a desert without end. No doubt. No faith. I would prefer him to have what we call a happy death."

"What do you mean by a happy death?"

"I mean the hope of something further."

"The beatific vision and all that nonsense? Believing in some life eternal?"

"No. Not necessarily believing. We can't always believe. Just having faith. Like you have, Sancho. Oh, Sancho, Sancho, it's an awful thing not to have doubts. Suppose all Marx wrote was proved to be absolute truth, and Lenin's works too."

"I'd be glad, of course."

"I wonder."

They drove for a while in silence. Suddenly Sancho gave the same yapping laugh that Father Quixote had heard in the night.

"What is it, Sancho?"

"Last night before I slept I was reading your Jone [Ed: Fr. Heribert Jone] and his Moral Theology. I had forgotten that onanism contained such a variety of sins. I had thought of it as just another word for masturbation."

"A very common mistake. But you should have known better, Sancho. You told me you studied at Salamanca."

"Yes. And I remembered last night now we all used to laugh when we came to onanism."

"I had forgotten Jone was so funny."

"Let me remind you of his remarks on coitus interruptus. That is one of the forms of onanism according to Jone, but in his view it is not a sin if done on account of some unforeseen necessity, for example (it's Jone's own example) the arrival of a third person on the scene. Well, one of my fellow students, Diego, knew a very rich and pious stockbroker. His name comes back to me--- Marquez. He had a big estate across the river from Salamanca, not far from where the Vincentians have their monastery. I wonder if he is still alive. Well, if he is, birth control will no longer be a problem-- he must be over eighty. But certainly it was a terrible problem to him in those days, for he was a great stickler for the rules of the Church. It was lucky for him that the Church had altered the rules about usury, for there's a lot of usury in stockbroking. It's funny, isn't it, but the Church can alter it's mind about what concerns money much more easily than it can about what concerns sex."

"You have your unalterable dogmas too."

"Yes. But with us the dogmas which are the most impossible to alter are just those that deal with money. We don't worry about coitus interruptus, only about the means of production--- I don't mean sexually. Please, at the next turning, take the road to the left. Now do you see ahead the high rocky hill with a great cross on top? That's where we are going."

"Then it is a holy site. I thought you were making fun of me."

"No, no, monsignor. I am too fond of you for that. What was I talking about? Oh, I remember. Senor Marquez and his terrible problem. He had five children. He really felt he had done his duty to the Church, but his wife was terribly fecund and he enjoyed sex. He could have taken a mistress, but I don't think Jone would allow birth control even in adultery. What you call natural birth control and what I call unnatural had consistently failed him. Perhaps the thermometers in Spain have been falsified under clerical influence. Well, my friend Diego mentioned to him--- I'm afraid in a frivolous moment--- that coitus interruptus was permissible according to the rule of Jone. By the way, what sort of priest was Jone?"

"He was German. I don't think he was a secular; they are most of them too busy to be moral theologians."

"Marquez listened to Diego, and the next time Diego went to his house he found that a butler had been installed. That surprised him, for Marquez was a mean man who did very little entertaining apart from the occasional father from the Vincentian monastery, and two maidservants, a nurse, and a cook were quite enough for the household. After dinner Marquez invited Diego to his study for a glass of brandy, and this surprised Diego too. 'I have to thank you,' Marquez told him, 'for you have made my life much easier for me. I have been reading Father Jone with great care. I admit that I didn't quite trust what you told me, but I have obtained a copy in Spanish from the Vincentians, and there it certainly is, with imprimatur of the Archbishop of Madrid and a Nihil Obstat from the Censor Deputatus--- the arrival of a third person does make a coitus interruptus permissible.'

"'How does that help you?' Diego asked.

"'You see I have hired a butler, and I have trained him very carefully. When a bell in my bedroom rings twice in the pantry he takes up position outside the bedroom door and waits. I try not to keep him waiting too long, but with advancing age I'm afraid that I sometimes keep him there for a quarter of an hour or more before the next signal--- a prolonged peal of the bell in the passage itself. That is when I feel unable to contain myself much longer. The butler opens up the door immediately and at this arrival of a third person I withdraw at once from the body of my wife. You can't think of how Jone has simplified life for me. Now I don't have to go to confesison more than once in three months for very menial matters.'"

"You are mocking me," Father Quixote said.

"Not a bit of it. I find Jone a much more interesting and amusing writer than I did when I was a student. Unfortunately in this particular case there was a snag and Diego was unkind enough to point it out. 'You read Jone carelessly,' Diego told Marquez. 'Jone qualifies the arrival of a third persom by classing it as "an unforeseen necessity." I'm afraid in your case the butler's arrival has been only too well foreseen.' Poor Marquez was shattered. Oh, you can't beat those moral theologians. They get the better of you every time with their quibbles. It's better not to listen to them at all. I would like for your sake to clear your shelves of all those old books. Remember what the canon said to your noble ancestor. 'Nor is it reasonable for a man like yourself, possessed of your understanding, your reputation and your talents, to accept all the extravagant absurdities in these ridiculous books of chivalry as really true.'"

The Mayor stopped speaking and glanced sideways at Father Quixote. He said, "Your face has certainly something in common with that of your ancestor. If I am Sancho you are surely the Monsignor of the Sorrowful Countenance."

"You can mock me as much as you like, Sancho. What makes me sad is when you mock my books, for they mean much more to me than myself. They are all the faith I have and all the hope."

"In return for Father Jone I will lend you Father Lenin. Perhaps he will give you hope too."

"Hope in this world perhaps, but I have a greater hunger--- and not for myself alone. For you, Sancho, and all our world. I know I'm a poor priest errant, travelling God knows where. I know that there are absurdities in some of my books as there were in the books of chivalry my ancestor collected. That didn't mean that all chivalry was absurd. Whatever absurdities you can dig out of my books I still have faith...."

"In what?"

"In a historic fact. That Christ died on the Cross and rose again."

"The greatest absurdity of all."

"It's an absurd world or we wouldn't be here together."

They had reached the height of the Guadarramas, a hard climb for Rocinante, and now they descended towards a valley under a high sombre hill which was surmounted by the large heavy cross which must have been nearly a hundred and fifty metres high; they could see ahead of them a park full of cars--- rich Cadillacs and little Seats. The Seat owners had put up folding tables by their cars for a picnic.

"Would you want to live in a wholly rational world?" Father Quixote asked. "What a dull world that would be."

"There speaks your ancestor."

from Chapter 5 ("How Monsignor Quixote and Sancho Visit A Holy Site") of Monsignor Quixote, 1982.

No comments:

Post a Comment